Courage to Challenge Conventional Wisdom

Why CEOs, not HR or insurers, who want to maximize shareholder and customer value must

Formative Experiences

From the time I was a child, I’ve been captivated by anomalies—those stray data points that don’t fit the pattern, but reveal hidden truths. While most people gravitate toward averages and generalities, I’ve always been drawn to the exceptions.

That instinct, first nurtured through sports and detective stories, became a lifelong habit. It shaped my legal career, my years as a CEO, and my philosophy as a leader.

Anomalies are often where the real breakthroughs hide. They can reveal a future trend before others see it, expose flaws that no one else notices, or unlock value that consensus thinking overlooks. They are uncomfortable to pursue because they challenge the story everyone else is telling. But again and again, I’ve found the biggest wins come from following the trail of data that seems “off.”

Sports and Outliers

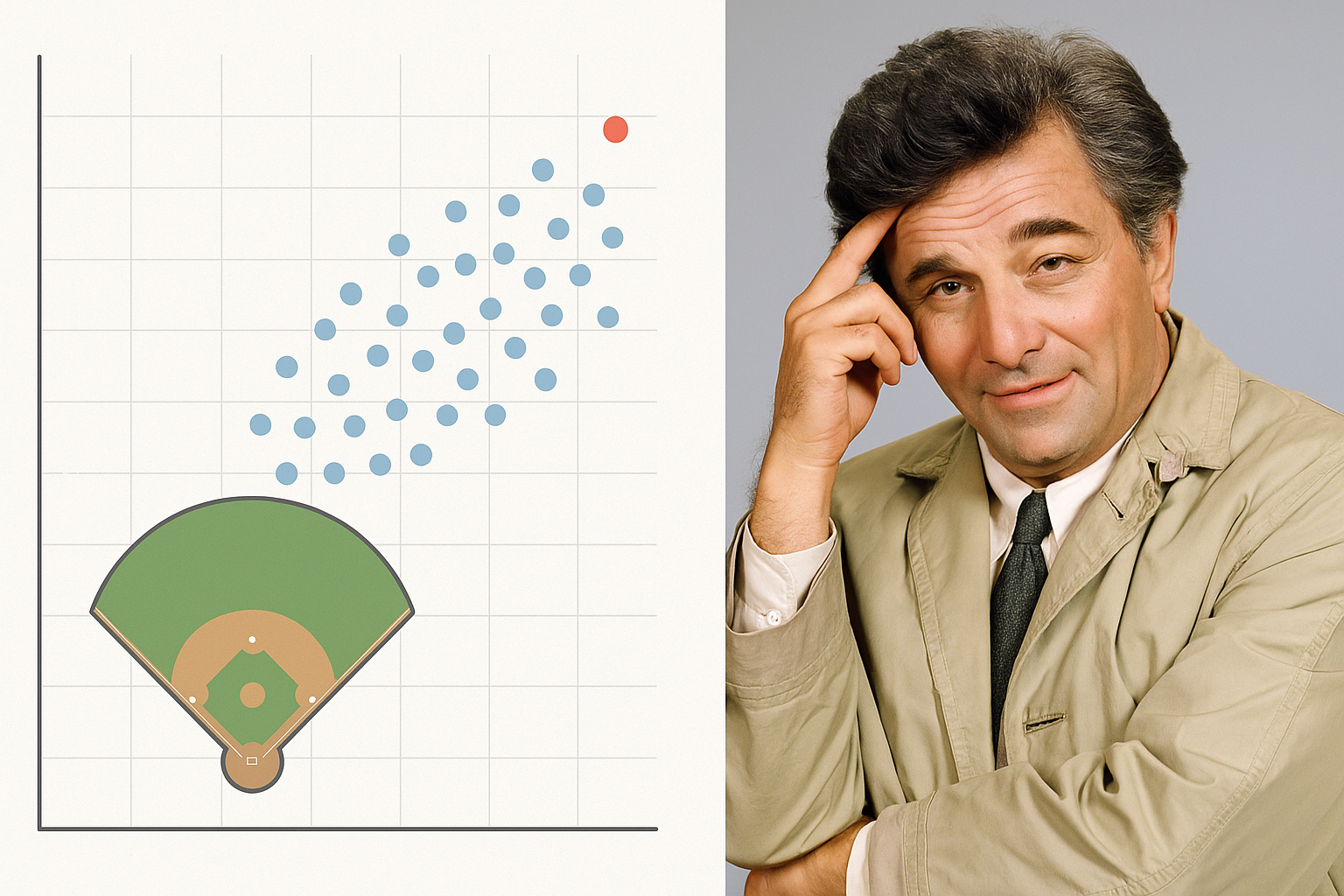

Baseball was my first classroom in spotting anomalies. While most kids obsessed over batting averages or home run totals, I devoured Bill James’s Baseball Abstracts, which urged readers to dig beneath the surface. James didn’t just crunch numbers; he searched for the data points that didn’t align with conventional wisdom.

Mariano Rivera is the perfect example. Early on, no one saw him as a star. His fastball wasn’t particularly fast in his career's early years. His minor-league record, although it signaled that he had some potential, did not stand out enough. But two anomalies set him apart: the effortless fluidity of his delivery and the late, wicked movement on his pitches. Those subtle differences became the foundation of the most devastating cutter in baseball history—and the career of the greatest closer the game has ever seen.

Wade Boggs was another. Scouts dismissed him because he lacked flash—he wasn’t a power hitter, nor was he fast. But one scout noticed an anomaly: his preternatural ability to avoid swinging at bad pitches. That discipline translated into a career .328 batting average, five batting titles, and enshrinement in the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Those lessons sank in. Don’t just look at what’s obvious. Look for what doesn’t fit—because in those small deviations, greatness often hides.

Mystery Stories and Detectives

Sports weren’t my only teachers. I grew up on mystery shows—Perry Mason and especially Columbo. Mason demolished prosecutors by finding and exposing contradictions in their narratives. Columbo, with his rumpled coat and “one more question” routine, relentlessly chased small inconsistencies until entire cases unraveled.

A suicide note that didn’t match a victim’s last actions. A stray item left behind at the crime scene. A calm suspect who suddenly lost his temper. Columbo’s genius wasn’t in encyclopedic knowledge—it was in refusing to ignore what didn’t fit.

That mindset influenced how I practiced law, and later how I led in business.

Legal Work and Anomalies

As a young attorney, I quickly learned that spotting anomalies could win cases. In one instance, both a business broker submitted a term sheet with the date “June 31,” a term sheet the contracting parties copied completely, including the non-existent date. That single error showed that the parties' assertion that the broker's actions had not been the catalyst to their merger was not credible.

In an investigation, a cash collection record appeared pristine—too pristine. The handwriting was identical throughout, and the ink was a vivid green, suggesting it had all been filled in at once. That anomaly cracked open proof of falsification.

Over time, I didn’t just notice anomalies—I trained myself to look for them deliberately. I usually asked: "What might we be missing?" They became my lever for uncovering truths others missed.

Using Outlier Data to Drive Business Value

Rethinking Healthcare Spending

In 1991, I encountered the Dartmouth Atlas Project, which documented how healthcare costs varied dramatically across regions. The prevailing assumption was that higher spending equaled better care. But the Atlas revealed the opposite: some of the lowest-spending areas had the best outcomes. That anomaly exploded the industry’s consensus.

At Pitney Bowes, we acted on that insight. We wanted to understand what the low-spending, high performing areas were doing. Instead of paying blindly for more services, we:

The result? For years, our healthcare costs grew more slowly than industry benchmarks—an enormous competitive advantage.

Customers Willing to Pay for Speed

In the 1990s, we noticed something odd: customers paid $25 for expedited postage advances, even though cheaper options were available from other sources. Why would anyone pay more? The anomaly revealed a deeper truth—customers valued speed and control more than marginal cost.

That insight led us to acquire a banking charter to offer credit lines to our creditworthy customers, manage over $600 million in balances. All because we followed a data point that didn’t make sense at first glance.

The Misplaced Event Invitation

One day, an invitation to a nonprofit gala crossed my desk. The envelope bore a competitor’s postage imprint, even though the nonprofit used our meters in-house. The anomaly pointed to a new market reality: mailings were increasingly outsourced to vendors using integrated equipment. The equipment driving which meter was chosen was upstream competitive equipment better suited for direct mail marketers.

That small clue pushed us to invest heavily in direct mail services. Through acquisitions and innovation, we became leaders in that market.

Learning from Our Top Inventor

After securing a $400 million settlement from Hewlett-Packard for patent infringement, I asked: what made our lead inventor, Ron Sansone, different? To a greater extent than other engineers, he didn’t just chase elegant solutions. He focused more on studying and anticipating where markets were heading and built commercially relevant technologies.

The anomaly was clear: the most valuable inventors weren’t necessarily the most technically brilliant—they were the ones who allocated more effort on market foresight. That insight reshaped how we evaluated and rewarded innovation across the company, and what behavior we wanted to promote.

Listening Differently

Skip-Level Meetings

As CEO, I refused to rely solely on filtered reports. I conducted over 150 skip-level meetings, visited field offices, and struck up conversations in community settings. Employees often shared small frustrations or workarounds they thought insignificant. Many of those comments were anomalies—tiny signals of bigger problems or hidden opportunities. Spotting those outliers gave me insights no dashboard could deliver.

Asking the “Off-the-Wall” Questions

I also asked questions that seemed, at first, irrelevant. Early in my tenure, some colleagues thought I was disorganized and focused on peripheral issues. But like Columbo, I had a mental map, and when something contradicted it, I wouldn’t let go.

One persistent anomaly involved cost-saving initiatives. Teams projected millions in savings, but headcounts never fell. Pressing further, I found the truth: workload reductions were spread across many employees—20% here, 15% there—making it nearly impossible to eliminate entire positions. The data looked impressive, but the anomaly revealed the reality: real savings were often unachievable.

The Andy Grove Influence

Andy Grove’s Only the Paranoid Survive hit me like a thunderbolt. Grove taught that leaders must spot “strategic inflection points”—the subtle signals that markets are shifting. By the time those signals are obvious, it’s too late.

That reinforced my conviction: anomalies aren’t noise. They’re often early warnings. They’re glimpses of the future breaking through the present. They are also signals of unexploited opportunities. The leaders who notice them—and act—gain a decisive edge.

Summary: The Courage to Notice and Stand Out

From baseball to detective fiction, from the courtroom to the boardroom, my career has been significantly influenced by the principle that anomalies matter.

Most people overlook them because they’re inconvenient. They disrupt neat narratives. They force us to question the consensus. But if you want to create lasting value—whether in business, health, or leadership—you can’t ignore the stray data point that doesn’t fit.

The outsized value lies there.

And yet, I often wondered why more leaders didn’t follow this path. The uncomfortable truth is that many aspiring executives would rather blend in than stand out. They echo consensus because it feels safe. They avoid anomalies because anomalies make us look contrarian.

But comfort never produces breakthroughs. Following the anomaly is harder. It can be lonely. It can make others bristle. Yet it is also the surest way to uncover hidden truths, seize new opportunities, and transform organizations.

The leader who notices what others ignore—who has the courage to chase the outlier data—will endure the discomfort of standing apart. But in the long run, they will also enjoy the twin rewards of outsized success and undeniable impact.